|

|

Barringer Meteor Crater -

photo by B.P. Snowder

|

When a large meteor strikes it can blast out a crater,

like one did 25,000 years ago: the Barringer Crater near Winslow Arizona.

About 1.2 km across and .2 km deep,

the meteor that caused it is estimated at 50 meters diameter

which would have weighed about 300,000 tons.

The Barringer meteor was very small compared to the object that created the Chicxulub Crater

in the Yucatán 65 million years ago. That is the one

that is theorized to have led to mass extinctions. It is estimated to have

been 6 to 15 kilometers in diameter.

Meteors are sometimes called "shooting stars" or "falling stars."

Most are only bits of gravel the size of your fingernails or smaller.

They are the leftover debris from the formation of the solar system.

Many are part of rivers of debris scattered by passing comets. If the Earth passes through

one of these rivers of debris, we have a meteor shower. Occasionally the Earth passes through a very

dense area of the river, and we have a meteor

storm with hundreds of thousands of streaks per hour.

-

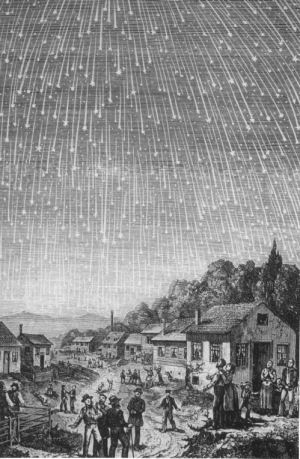

"On the night of November 12-13, 1833, a tempest of falling stars broke over the earth...

the sky was scored in every direction with shining tracks and illuminated with majestic fireballs.

At Boston, the frequency of meteors was estimated to be about half that of flakes of snow

in an average snowstorm. Their numbers ... were quite beyond counting; but as it waned,

a reckoning was attempted, from which it was computed, on the basis of that much-diminished rate,

that 240,000 must have been visible during the nine hours they continued to fall."

~ Agnes Clerke

|

|

Engraving of the 1833 Leonid Meteor Storm

|

When the Earth runs into a patch of debris that is all moving parallel, like the stuff left by comets,

it looks like the

streaks radiate outward from a particular point in the sky. This happens for the same reason that

parallel train tracks appear to converge to a point on the horizon. It's just perspective. The streaks in

each of the major meteor showers appear to radiate from a point in a particular constellation as the

Earth reaches a certain point in its orbit each year. This is what gives the names to the showers.

When a meteor

happens during a shower but doesn't radiate from the point like the rest, it is called a rogue

- not a true member of the stream.

On the other hand when a true member of the stream comes days earlier or later than the

rest of the herd, it is called a stray.

The best time to see meteors is between midnight and dawn. That's when you are on the part of the Earth

that is "in front" as it travels through space. In fact, at dawn you are on the very bow of the ship.

On an average day about 4 billion meteors enter our atmosphere, totaling more than a hundred tons.

Debris enters the

earth's atmosphere and gets heated by friction because it travels at such high speed,

10 to 70 kilometers per second. For a few seconds

they streak across the sky. The brightness we see is actually the hot ionized gasses surrounding

the object. Usually the object

completely burns up before hitting the ground, but some are large enough to

survive and impact the ground. These are called meteorites.

Sometimes a meteor will enter the atmosphere weighing several kilograms.

these are spectacular events called fireballs.

The glowing trail following fireballs sometimes continues to glow for up to 30 minutes.

Fireballs are typcially the brightest objects in the night sky. If you see a fireball,

remember to take a quick look at how distinct your shadow is.

Also, listen carefully, sometimes fireballs explode. Exploding meteors are called bolides.

|

Major Meteor Showers

|

Shower |

Peak Dates |

Meteors/Hr/Observer |

Associated Object |

| Quadrantids |

Jan. 2-4 |

40-100+ |

unknown |

| Lyrids |

Apr. 21-22 |

10-15 |

Thatcher |

| eta Aquarids |

May 4 |

20 |

Halley |

| delta Aquarids |

July 29 |

15-20 |

unknown |

| Perseids |

Aug. 11-13 |

50-70+ |

Swift-Tuttle |

| Draconids |

Oct. 9 |

6 |

Giacobini-Zinner |

| Orionids |

Oct. 21 |

25 |

Halley |

| Taurids |

Nov. 3-5 |

15 |

Encke |

| Leonids |

Nov. 17 |

10-20 |

Temple-Tuttle |

| Andromedids |

Nov. 25-27 |

5 |

Biela |

| Geminids |

Dec. 14 |

50-80+ |

3200 Phaethon |

| Ursids |

Dec. 22 |

5 |

Tuttle |